A few weeks ago, at Hobby Lobby, I slid three candles across the counter in the shapes of 1, 0, and 0. I try to avoid Hobby Lobby when I can. The lines are always slow, and what’s worse, the slowness is a result of the interrogation that happens at the check-out counter.

“Oh, someone’s turning 100,” my cashier said, the kind of statement that’s really a question.

“Yes,” I said. “Well, kind of.”

I could see where this was going, and I dreaded getting into the weeds. I didn’t have it in me that day. But then again, I didn’t have the energy to come up with a lie either.

“Is it a family member?” she pressed.

Here we go.

“Flannery O’Connor would be turning 100 in a couple of weeks,” I said, watching her face for some flicker of recognition. When the confusion steadily burned, I pressed on. “She used to be a writer, but she died sixty years ago. I’m throwing her a party with some friends.”

The cashier’s lips twitched like they wanted to say something but they were waiting on the brain to tell them what. The brain had no further instructions, it seemed.

“We hope she doesn’t show up,” I said, winking. Humor usually helps in situations like this. She laughed, relieved, and slid the receipt into my bag.

But the truth was that I wished Flannery O’Connor could show up to her party—not in a ghostly sense, of course, but with her flesh on, both body and soul. It would be nice to sit down with her over a piece of birthday cake, and to talk about writing.

I encountered O’Connor’s work only eight or so years ago. First, her short stories, which I found both difficult and disturbing. She would have been pleased to hear it, since her self-righteous reader was meant to be disturbed. But, as she once wrote to a friend, I began as a reader who had “hold of the wrong horror.”1 I was horrified at the violence, at the way she forced my gaze toward the grotesque, at the bleak endings. I didn’t know, until much later and with some help, that I was meant to be horrified by my own pride. I didn’t know that I was meant, by her stories, to be stripped bare, to watch even my virtues be burned away.2

Once I realized what O’Connor was up to in her fiction, I started to enjoy it. I even laughed—because, as it turns out, she was incredibly funny. This is because the world is funny, and O’Connor was someone who paid attention. Seeing the world clearly is one kind of gift, and O’Connor had it in full measure. But she also had the gift of accurately naming what she saw. She could both “see straight and write straight.”3 I’d say it’s unfair for one person to have so many gifts, except that we’re all better for her having them. And it’s only unfair in the sense that we didn’t deserve her—someone who acted like a prism for us: who was able to take in the world as it was and give it back to us, refracted into astonishing hues.

When I turned 40 last spring, I outlived Flannery O’Connor. She died at 39 of lupus, having written more in her short life than most people do with twice the time and all the health in the world. On my birthday, I felt no great existential crisis, no sinking dread, nothing like my friends had warned me about. If anything, I was pleased to be 40. But when Ethan Hawke’s biopic Wildcat came out the next month, I took a bit of a nosedive. After watching this movie about her life, I was no longer just considering Flannery O’Connor’s writing, but her whole way of being in the world. I was astonished at how doggedly she pursued her calling in the short time she had.

For someone her age, she understood what she was about with an unusual clarity. She was serious about her calling as a writer. She was prayerful about it. She made herself a servant of the work: sitting at her writing desk every morning, reading widely, sending off her work for publication, pulling in trusted friends to help her craft the perfect phrase. I never expected to out-write Flannery O’Connor, but when I held up the habits of my own life next to her’s, I couldn’t help but feel the weight of comparison. At 40, I didn’t feel I was taking my life and my calling anywhere near as seriously as she had in her 30s. I felt crushed at the thought, and ashamed, and, honestly, a little depressed.

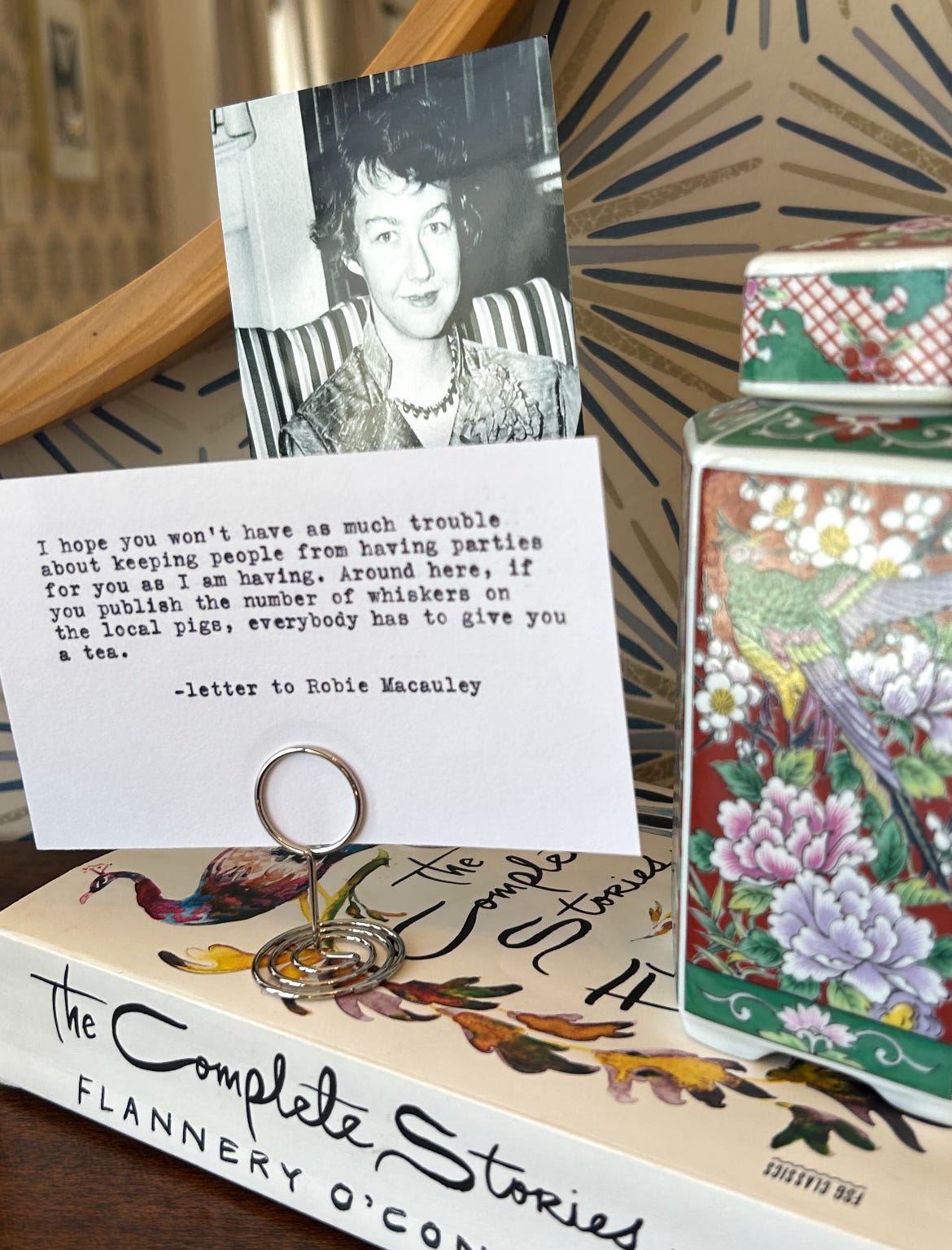

And then, earlier this year, through a series of events too winding to recount, I found myself planning a birthday party for Flannery O’Connor. She had a previous engagement (eternity), but by smiling providence, my friend Jonathan Rogers was set to be at my house on March 25th, which would have been her 100th birthday.

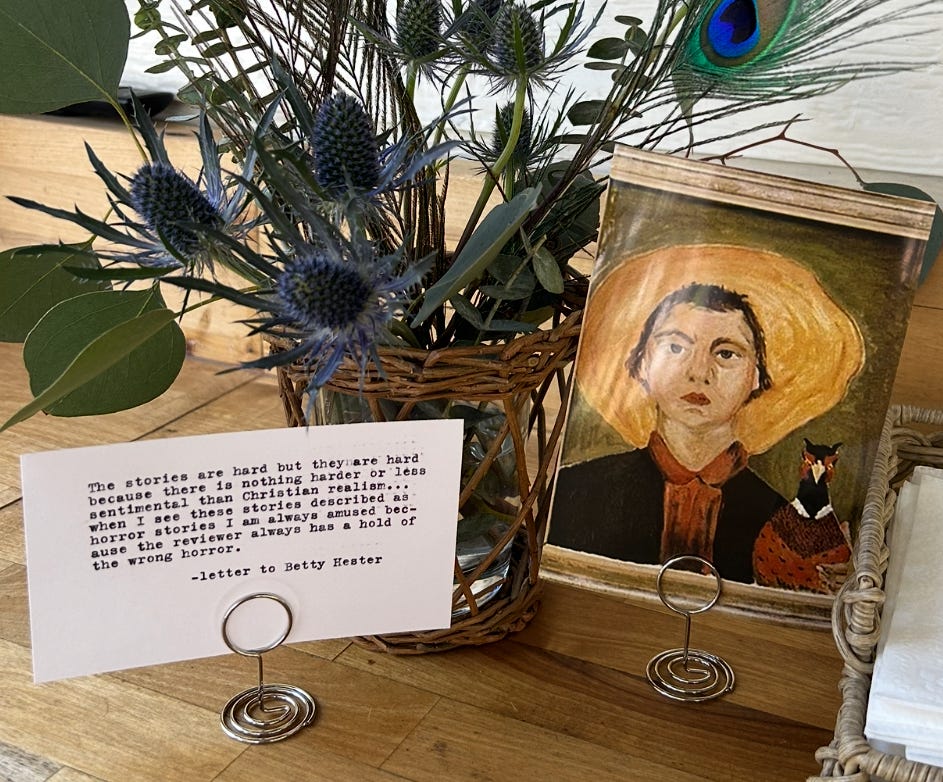

Jonathan wrote The Terrible Speed of Mercy, a lovely portrait of O’Connor, which I read the same summer I watched Wildcat. He’s the reason I ever stopped being horrified at her stories, and became horrified by them, which is to say, he’s the reason I learned to read her right. At some point, I realized it would be more absurd not to throw this party than to throw it. So I sent out some invites with this quote…

I hope you won’t have as much trouble about keeping people from having parties for you as I am having.

Flannery O’Connor

Letter to Robie Macauley

May 2, 1952

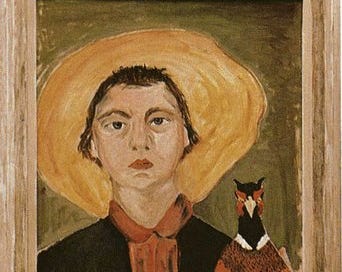

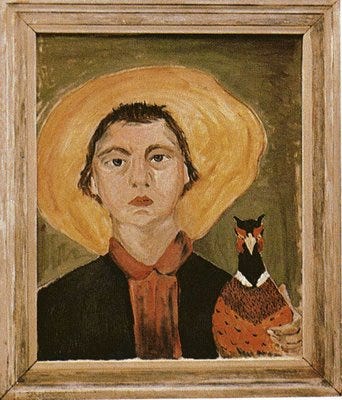

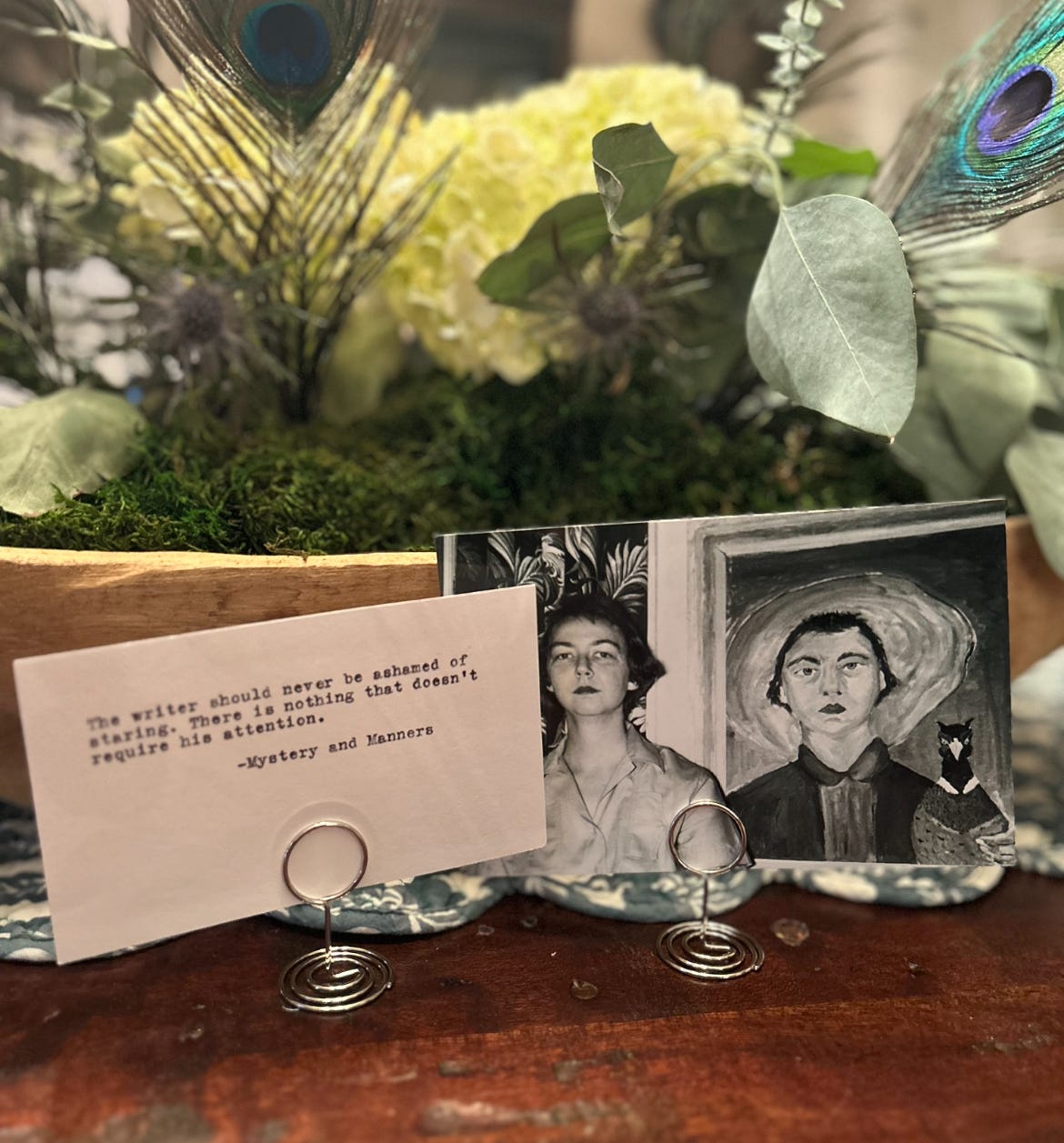

…and with this self-portrait that O’Connor painted in 1953.

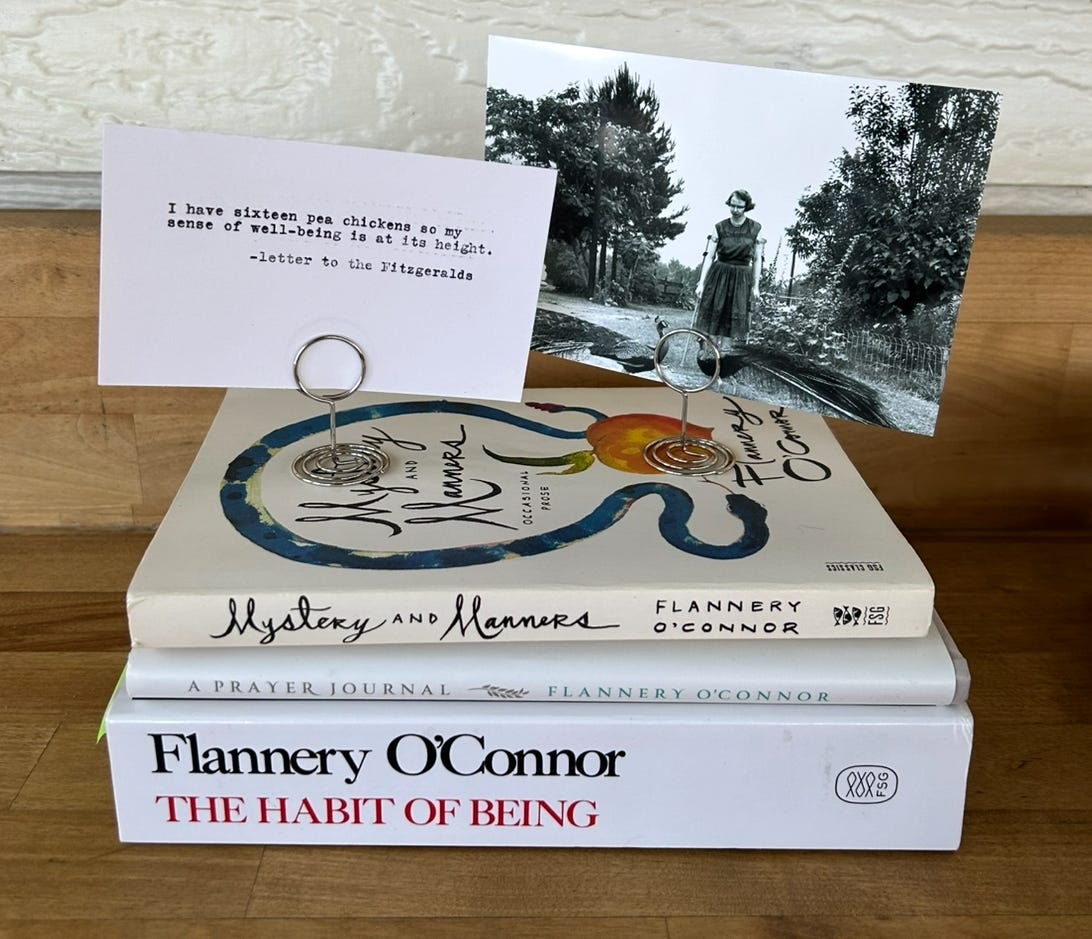

More importantly, while getting ready for the party, I picked up The Habit of Being, a collection of O’Connor’s letters compiled by her friend Sally Fitzgerald. In the introduction, Fitzgerald regrets that the camera did O’Connor no favors. Her friends often wished they had some true record of how she looked to them, since photographs didn’t do her justice. “I have come to think that the true likeness of Flannery O’Connor will be painted by herself,” Fitzgerald writes, “a self-portrait in words, to be found in her letters.”

She was right. These letters let me see O’Connor as a whole person. Not someone to measure myself against, but someone to love. Someone I wished I could sit on the front porch with, swapping stories.

Flannery O’Connor spent most of her adult life separated from the writing community she had found in New York. Her declining health brought her back home to her mother’s farmhouse in Milledgeville, Georgia where most of these letters came from. In her letters was a woman who was fiercely loyal, both humble and self-assured, a friend who grieved with those who grieved and laughed with those who were merry. She wrote about theology and the daily goings-on at the farm where she lived with her mother and her beloved peafowl. She handed out writing advice freely. Mostly, she was someone who was hungry for friendship. Mail, she said, was very eventful for her. She often ended her letters with a simple plea: “Let me hear how you do.” Don’t you love her for that?

But it’s this business about the self-portrait that’s made me really love O’Connor. I like that Sally Fitzgerald calls her letters that too—a self-portrait. One has to think it’s a nod to the portrait O’Connor painted of herself, with her arm around that smug-looking pheasant, and that golden sunhat encircling her head like a Byzantine halo. O’Connor painted this portrait after suffering an acute episode with lupus. She told her friend Elizabeth Lowell in a letter that her hair had just fallen out from a high fever, and she had what they called “moon-face” as a side-effect from the cortisone. “When I painted it I didn’t look either at myself in the mirror or the bird,” she wrote to Lowell, “I knew what we both looked like.”

O’Connor was so proud of that painting she took photographs of it and mailed them off to to pen pals and publishers alike. I’m only halfway through her letters, and I’ve already counted six people she’s mentioned it to. You have to admire that kind of confidence.

Here’s what she had to say about the portrait in her letters:

I painted me a self-portrait with a pheasant cock that is really a cutter but Regina keeps saying, I think you would look so much better if you had on a tie.

Letter Sally and Robert Fitzgerland

Summer of 1953

The enclosed is a snapshot of my self-portrait. Maw says it shows exactly how awful it is but it don’t really show how good it is because the colors are nice in the original.

Letter to Sally and Robert Fitzgerald

April 26, 1954

Nothing has been said about a picture for the jacket of this collection but if you have to have one, I would be much obliged if you could use the enclosed so that I won’t have to have a new picture made. This is a self-portrait with a pheasant cock, that I painted in 1953; however, I think it will do justice to the subject for some time to come.

Letter to her publisher, Robert Giroux

January 22, 1955

I’m glad you like the self-portrait. The colors are real nice too. I’m sorry you can’t see the colors…

Letter to her literary agent, Elizabeth McKee

June 29, 1955

I am the one on the left; the one on the right is the Muse. This is a copy of a self-portrait I painted three years ago. Nobody admires my painting much but me. Of course this is not exactly the way I look but it’s the way I feel. It’s better looked at from a distance.

Letter to pen pal, Betty Hester

October 20, 1955

Aren’t these great? There’s no false humility here, no desperate need for praise. Just a matter-of-factness that I admire: I made this thing. I think it’s pretty good. I want you to see it, too.

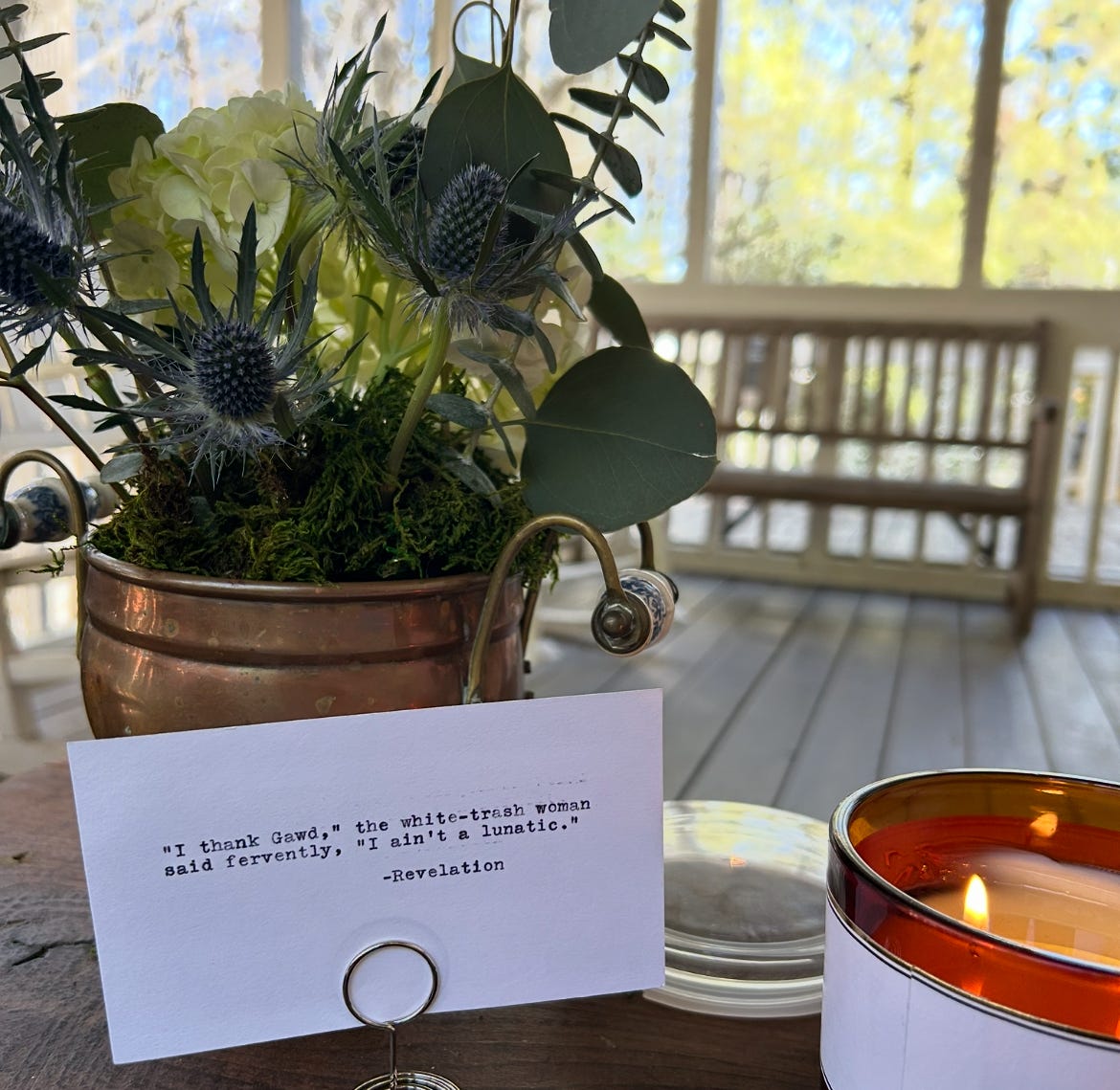

Last Tuesday night, I sat on the back porch with some friends who wanted to talk about Flannery O’Connor. We marveled at her gifts, her turns of phrase, her uncanny ability to shake the spiritually dead awake. We read favorite passages from of her writing, and raised birthday toasts in her honor. Jonathan read a blessing over us: A Prayer to Saint Raphael, the angel of happy meetings, a prayer which O’Connor prayed each morning.

Among us were mothers, geology professors, librarians, gardeners, woodworkers, teachers, painters, and, of course, writers. And I thought about how, in one way or another, we were all makers. We’re all taking the raw materials of this life we’ve been given and trying to make something beautiful out of it.

O’Connor was a woman who worked with what she was given—illness, isolation, a sharp mind, an eye for the grotesque, a deep-rooted faith, a typewriter, a yard full of peacocks. She took those materials and made something only she could make. And in the process, she came to look more like herself. More like her self-portrait. Or at least, her soul came to look more like its true self—glowing with sainthood, as one united to Christ himself, even as her flesh failed her. “Of course this is not really the way I look, but it is the way I feel…”

We too are all little self-portraits, in this same mysterious partnership with the Lord—coming to look more like our true selves as we make things, call them good, and send them off into the world.

O’Connor never cared much for parties. More than once, she admitted in her letters that she left them feeling as if she hadn’t said a single intelligent thing. (I empathize with this.) She’d be pleased to know that at this party, we let her writing do the talking, and she sounded plenty intelligent. And better still, a color photograph of her self-portrait sat by the cake table, and another copy kept us company on the back porch. I believe she’d like that. The colors are real nice. And you were right, Flannery, it will do justice to the subject for some time to come. Happy birthday.

And now, Reader, in my thickest Southern drawl: Let me hear how you do…

“The stories are hard but they are hard because there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realism… when I see these stories described as horror stories I am always amused because the reviewer always has hold of the wrong horror.” —Flannery O’Connor in a letter to Betty Hester, from The Habit of Being.

“Yet she could see by their shocked and altered faces that even their virtues were being burned away.” —from her short story, “Revelation”

“It’s a very pompous phrase—the accurate naming of the things of God—I’ll grant you…But then I said it was a basis. What I suppose I mean is an aim. Anyway, I don’t mean it’s an accomplishment. It’s only trying to see straight and it’s the least you can set yourself to do, the least you can ask for. You ask God to let you see straight and write straight.” —Flannery O’Connor in a letter to Betty Hester, from The Habit of Being

I know you spent more than a few hours in the writing of this. Hours that you could've spent some way else, such as weaving your family clothes, or bedsheets, from scratch. But I hope you will consider how the Lord feels about those hours.

Consider whether he might feel those hours were the hours he was secretly hoping you'd be bent over word-work, which for a writer is the distillation of love.

I bet he wanted to be on that party porch, too, talking about whether he himself was much of a woodworker, marveling at Flannery's peacocks and Elizabeth's cake, laughing at every wonderful joke together with you folks! I bet he wanted to be there---and---I know he was. I can sense it from way over here in Minnesota. I could spend 10 hours reading this beautiful distillation, and not one would be wasted. I feel so lucky to have a friend who appoints herself party-thrower and then also answers my letter pleas to wrap all of us right up in the celebration.

"I have other things to say but they can wait and you will have had enough of my incoherence." -from a letter to Betty Hester

If you ever stop writing to weave your family’s clothes or bedsheets from scratch, I will protest.