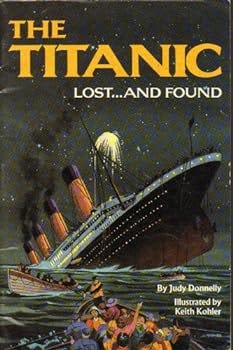

In 1912, the RMS Titanic gave a long groan and sank into its watery grave. Eighty years later, I collided with this ship in my fourth-grade classroom during free reading time. My heart dashed against the book cover on Mrs. Hicks’s bookshelf.

I stared at the small people, in their small lifeboats, who were staring in frozen astonishment at half of a ship standing upright in a black ocean. I whispered quietly to myself, “Oh no.”

I took the book back to my seat, beside Derek Manis with his long, blonde rat tail, and I read through sentences quickly. I scanned and skipped over words, leapt from paragraph to paragraph. I read frantically, hungrily, as one would read a letter of distress from a loved one. Derek took a noisy bite of his apple. Women and children disappeared into the cold North Atlantic. I laid my head down on the desk, and listened to the rustling pages of other books in the room. Those poor people, in that tragic boat, sank down and down into my very bones.

I pushed my food around the dinner plate, and thought about them. I sat quietly on the swings at recess, and thought about them. I laid in bed at night, and placed myself on the deck of the ship as it was sinking— What would it be like to look down at the sea that was about to swallow me whole? What would I hold onto if the ground beneath me was my enemy? What would I think about as I stared at the small people, in their small lifeboats, who were staring back at me?

I stacked books on my bedroom desk like I was the next person tapped to preserve the Titanic’s history. And when the blessed internet came to my house a couple of years later, I researched survivor lists, and underwater wreckage footage, and China patterns used in the First Class dining room.

It’s hard to say why I was so captivated by the Titanic. Maybe it was the ability to take such long gazes a catastrophic event that posed no threat to me. I certainly didn’t have any plans to go on a maiden voyage across the Atlantic, and definitely not in 1912 when they didn’t think about things like everyone needing a seat on a lifeboat. Looking at the Titanic was a bit like staring straight at the sun—this burning and terrible image of death—with no consequences for the staring.

Christmas of my eighth grade year, Titanic came to the big screen. The middle school hallway was abuzz with whispers about the heart-throb, Leonardo DiCaprio. And while I’m not saying I wasn't interested in that, what I am saying is that I was more interested in the boat itself, and the events of that night, unfolding before me in live-action.

I sat in a crowded theater with my best friend, Tamara, who was definitely there for Leo. Sure, she knew what the Titanic was, but she hadn’t spent a third of her life thinking about it. By the end of the movie, she was heaving sobs into a popcorn-greased napkin. I gave her a side-eye, because what was she crying about? I craned my neck around to witness more unearned grief pouring out all over the theater. I got uncomfortable. I didn’t like all of these people in this crowded theater adopting the Titanic as their own personal tragedy, because somehow it belonged to me. I knew that minutes later, they would walk outside into the blinding sunshine, stretch their arms over their heads, and ask what’s for dinner, or what song should we play next?

Weeks went by and it seemed that everyone was talking about the Titanic. They were talking about it on the morning shows; They were talking about it at the Christmas dinner table; They were talking about it at the mall. There were Titanic posters, and Titanic drinking glasses, and Titanic sweatshirts. When we returned to school after Christmas break, Jennifer said she saw the movie eight times. Eight! She said it like a challenge— like “Who can beat that?” But we all knew that none of our parents were going to pay for nine movie tickets.

When I went back to the library to check out another book on the Titanic, I couldn’t find any on the shelf. I asked the the librarian for help and she gave me a knowing glance. Oh yes, another middle school girl coming to live in the world of Jack and Rose.

”Of course, honey, they’re all together on that table right over there.” Oh no, a themed table at the library. It was a trend now. A craze. A mania. And so I abandoned my post as my generation’s Titanic expert. It looked like there were plenty of us now, and suddenly it wasn’t quite as interesting.

To me, this has always been a funny little story about how I avoid being mainstream. I don’t read the popular book that everyone else is reading; I refuse to listen to the new Taylor Swift album; If you’re all listening to the same podcast, then it’s probably not the one for me. And how rude of everyone to start paying attention to the Titanic.

But now, revisiting this story, I’m more captivated by the thought about being in the audience of tragedy. How easy it was to stare straight into the heart of a loss, to care deeply about it, and then to walk away. Of course, I didn’t really know anyone on the Titanic, so this abandonment wasn’t felt by anyone but my own self.

But it’s not the only time I’ve untangled myself from someone else’s grief, and I suspect you’ve been able to do the same. How often have I been one of those small people, in those small lifeboats, staring in frozen astonishment at half a ship upright in a black ocean. What can we do, but grieve for the tragedy before us—and then walk into the blinding sunshine of our life on dry land, and ask what’s for dinner.

And when we are the ones whose lives are dashed against surprising grief, when we stare at the cold waters about to swallow us whole, everyone around us will look so small. Maybe even our own spouses, beside us in the bed, skin against skin, will seem to be in their own boats miles away. Maybe all anyone can do is watch us snap in half and disappear inch by inch into the mouth of sea. We scan the horizon looking for Jesus, who is supposed to be there, but who is not there.

But as we go down, we will find that Jesus is not in a boat, staring in frozen astonishment. He is not even in the waves with us. He is the ocean that we sink into— down and down into His very bones.

And in the blinding sunshine of the other side, He will pull up a chair and ask: What would you like for dinner? And what song should we play next?

And what about you Reader? Did you have a phase with the Titanic? Did you have another catastrophic event that you obsessed over as a child? I would love to hear about it!

My first bonding to another's suffering was when I was very small. I saw a Time magazine with a boy with iron arms or legs in the cover. I just stared. I may have been almost 4 because I remember the house we were in. I just cried and stared and hurt. I even write a small story of it. The second was walking by a black and white TV. My dad was watching Imitation of Life. A white boy was beating a girl in an alley against a dirty wall. Calling her ugly names. I stood, paralyzed with terror. I asked him what he was doing and my dad just said he was mad because he'd found her mom was black. That's it. I probably was about 7. I can't tell you the horror that shrouded me with. I couldn't understand meanness and cruelty. And poverty too. I don't think I ever walked away from this. My heart just broke but I never understood. When Titanic came out I was out of all normal loops raising my kids and it sounded more like a hit romance so I never really got involved. Biafara starvation and migrant oppression and black rights, MLK being killed...all carried in my heart and mind was so much overload to bear. But oh how I've tried to!

I know I was enthralled (and horrified) by stories of volcanic eruptions, but not a specific one. I do remember my fascination with WWII events in the Philippines. We lived there from the time I was five to nine and saw numerous sites like the monument at the end of the Bataan Death March and the island of Corregidor. I remember someone driving us somewhere and pointing to little caves in tucked in the brush and telling us about Japanese soldiers beings found there years after the war who didn’t know it was over. Years later, when I met Kraig’s grandfather we bonded over his memories of being in the Philippines during WWII. I came to find out that he started to tell stories then that he’d never shared.